Why me

Text: Hasmik Hovhannisyan

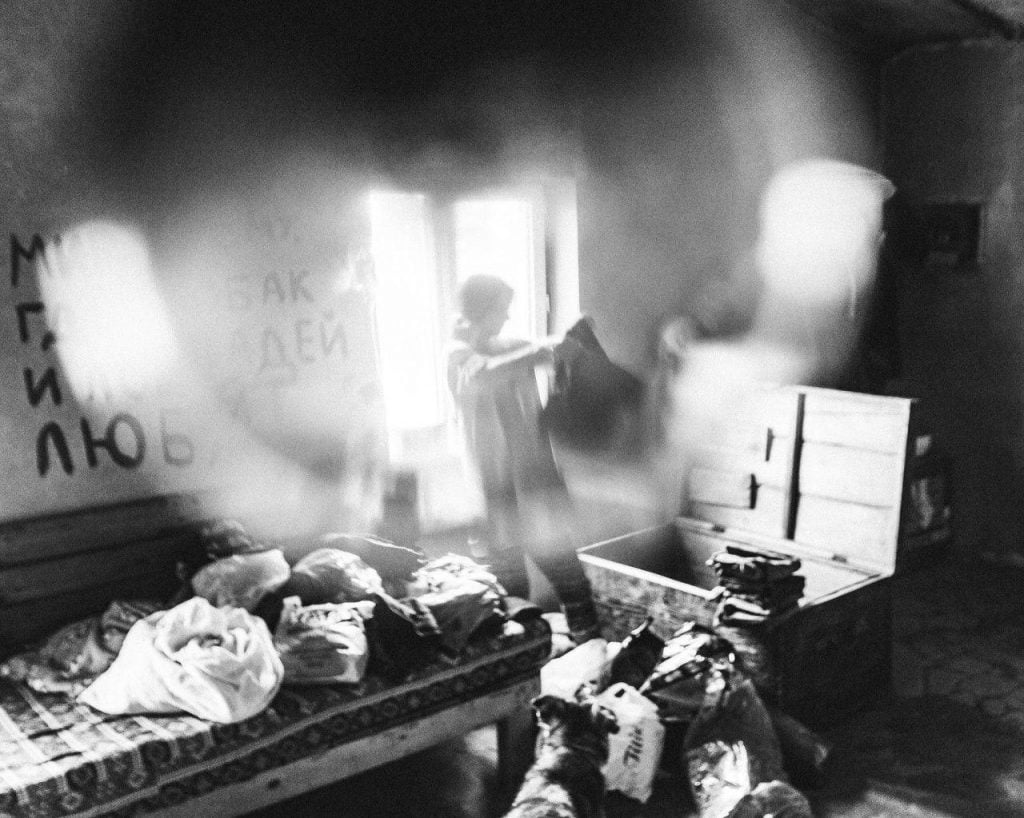

Photos: Fëdor Kornienko

[post_published]

[show_post_categories show=”category” hyperlink=”no” parent=”no”]I live in imaginary worlds from books. All characters are either knights or villains. It’s easy to distinguish the villains: they feature a stern face with a fierce look, and always wear dark clothes. But it turns out that in the real world even a villain can wear a soft smile and a light shirt.

10 min read

My fault

I’m thirteen. I love Freddie Mercury. Every Friday, I get on a yellow bus and drive off to “the faraway lands”, as it seems to me, for forty minutes. My destination is precious to me, it is a small underground booth that sells music cassettes, including Queen’s. They are gradually moving into my big box.

I am sitting in the back seat of a crowded bus, sandwiched between two adults, firmly pressing my hand to the side pocket of the backpack, where I’ve got the money for the purchase, and smiling.

A full-figured woman sitting next to me is chatting with her friend, and her body bounces with laughter, almost throwing mine into the air. But soon the unusually strong April heat wears them out, and the crowded bus slowly submerges into the state of sleep.

I also start getting dozed off for a while, but then I feel a hand touching my knee. I open my eyes. The hand of an elderly man sitting next to me. I remember him smiling warmly, as a grandfather would, as he moved to the window seat to make space for me when I got on the bus.

A wrinkled palm slightly squeezes my bare knee, and then moves closer to the shorts. I turn my face to the man. He is looking out the window, his face impenetrable. His hand halts. I strain my leg and release it from under his palm. Then I secretly look at the people around. No one is looking at me. No one saw anything.

The hand reaches for my knee again. The man smiles with the same warm expression and again turns to the window. I squeeze myself deeper into the seat. My own palms are sweating from horror. What do I do now? Should I confront him? But what if he gives me a surprised look and says that I imagined it all, only for me to feel very stupid?

Shake off his hand again, I’m telling myself. So that no one will notice. I shouldn’t have worn shorts. It’s good that at least I didn’t put the blue ones on, those are even shorter. Then get off at the next stop. But what to do then? Where even am I? The “faraway land” should be, well, still far away, and the rest of the route is unfamiliar to me. I only know how to get to the cassette booth from the bus stop near the metro station.

And I stay on the bus to the very end, releasing my foot persistently from under the sweaty wrinkled palm. I take off at my stop and run, choking with disgust and despair.

I am a timid girl with an exaggerated sense of responsibility and in a persistent state of guilt, life’s fitful fever. Almost in anything bad that happens around, I manage to see punishment for my own wrongdoings.

The bus incident is no exception. After all, what happened could happen only to me, and only due to my failures.

Every summer I’ve been wearing shorts and T-shirts. I can’t stand the heat so much that I would tear my skin off if it was possible. Among our family friends and relatives, literally no one ever missed the chance to reproach my mother for my inability to dress more “appropriately” — since I was eight.

Obedience, modesty, and some kind of special “quietness” are qualities that people usually cherish in girls. They need not draw attention to themselves — so that a good boy’s parents would notice, admire that, and plan marriage for when they grow up. Girls have to always keep their appearance and behaviour in check since they are to be future wives and mothers.

On the bus, I had at least one of the attributes of the “bad” girl I was warned about — the ill-fated shorts. Thus, there isn’t room for doubt — the adversity on the bus was my fault.

I’m thirteen, and I still don’t know that other girls — completely different from me — are also “touched”, that they, too, squeeze themselves into the seats and secretly look up to see if anyone noticed. It is easy to spot them around — usually, when they grow up they become women who carefully pick the people to be around their daughters — be it a swimming coach, a dance teacher, or a massage therapist, and they make sure those people are exclusively women.

Ashamed and scared

I am eight years old. I often stand in hours-long queues to buy bread with ration coupons. Sometimes impatient people squeeze me from both sides. It’s difficult to breathe, but otherwise, everything is normal. But suddenly I realize that that adult from behind somehow “isn’t right.” I begin feeling uncomfortable. It is not easy to explain and it’s scary to admit even to yourself, but you know for sure that something is wrong. It is difficult to give a name to this obscure anxiety, and to act on it, too.

I’m fourteen. We, the girls, are gossiping together in the classroom about those “maniacs” who have appeared in the city. They are terrible, disgusting, and they “do this and that…”

One day I’m going to school past the Lambada Bridge. Near the stone wall, there’s a man with his pants down. He is standing with his back to the road and I can feel that he’s doing something obscure, unpleasant, and terrible. It will take many years before I hear the word “masturbation” for the first time, as well as everything else about sex.

I lower my head and pick up the pace. Others — both adults and children — too, as if nothing is happening.

I see “maniacs” quite often. They have a lot of faces, but the man on the bridge shows up most often. One day he tries to chase after me with his penis that’s sticking out. The man has an infantile, unhealthy appearance and dirty mustard-coloured pants. It’s hard for me to run, I’m gasping in disgust and horror. Near the school and the neighbouring military base, he starts lagging behind.

After that, I start going to school by bus only for a few days. But then I decide that I don’t want to live in fear — and go to the bridge again. Sure enough, when approaching the Lambada bridge my feet are starting to walk faster and then run against my will.

Very soon I met that man again. He starts following. But then the fear that’s built up inside me suddenly turns into rage. At the underpass, I notice a thick tree branch with many little branches lying on the ground. At the time, the book I was reading at home was the second part of Romain Rolland’s “Enchanted Soul”, and I was very impressed by Asi, the Russian revolutionary rebel.

I stop, wait until the man comes closer, turn around, and strike him with all my might.

Enraged, I hit randomly without aim, but by luck, I hit the right spot. The “maniac” howls in pain, tries to protect himself with his hands, but the demon that woke up within me continues to whip and whip without mercy.

Then I drop the branch and run. I never knew how to run fast, but now I’m flying. It turns out that maniacs are not as scary as they are portrayed, it turns out that I am strong and can stand up for myself.

However, euphoria from my newly discovered strong self doesn’t last long and quickly gives way to despondency, guilt, and shame. Like then, on the bus.

Why didn’t I scream to the whole bus? To the whole street? Why didn’t I tell my mom when I got home? Because I am ashamed. How can I put such a thing into words? How not to die of horror at the moment when I open my mouth and begin to describe… this?

In addition, putting into words what happened to you, pronouncing these words out loud, you as a child irrevocably accept the fact that your world is no longer a safe place. Scary things happen here. And others — relatives and parents — will also have to admit it, and then act. I imagine my mom with heart drops in her hand and my dad who kills the “maniac” and gets imprisoned for life. It’s easier not to think, not to choose — and not to speak.

Many children walked along the same road: I don’t want to be a girl, I don’t want to be myself. A few seconds before I picked up the branch, the man muttered: “Delicious body.” I don’t fully understand what this means, I don’t know if it’s good or bad, but I want to get rid of this body, to stop identifying with it.

I start to dream that I am not myself. I imagine how the soul leaves the body and flies far, far away. In crisis situations today, I still do it sometimes.

Sometimes I’m self-loathing. I take a knife and cut my hands. Not the veins, no. I don’t want to kill myself. I just try to hurt something that I hate.

Inside, I have endless dialogues. I call myself “you”, as a different person. I separate the me-good, with whom shameful things cannot happen, from the me-bad.

You misunderstood

I’m sixteen. “Do you love me?”, the man asks. He is much older than me, he is one of the closest people to our family. Parents asked to bring a bag with ripe peaches to his house. I am mixed up. Anxiety appears. I immediately think that I am wearing shorts and a T-shirt.

“At your age, it’s time to dress more modestly,” a neighbor said in the morning, having seen me in the house yard. “Why do you always go outside half-naked?”, she looked disapprovingly at my regular clothes. Because it’s summer. I still can’t stand the heat.

The man gently strokes my head. He says I have a beautiful body. And pretty shorts. My anxiety intensifies. Again there is a desire to disappear, not to be. I don’t like standing here. I don’t like his smile. I want to turn around and leave. But I remain standing — with a tense body, and sweating palms — and smile stupidly.

“So show how you love me,” says one of my dearest people.

He throws me on the bed and presses me down with his whole body. I’m lost. I don’t understand what to do and what’s going on. “You are fluttering like a hunted beast,” — mentally me-good, watching from the side, says to me-bad.

This voice makes me wake up. The girl with a thick branch, violently beating the “maniac” flashes before my eyes. I bite my teeth into the hand near my face, with a force that wasn’t mine I hit with my knee into his stomach, and push his body off me. Surprisingly, the body crashes on the floor.

It’s the ground floor. Get up. Open the window, for it doesn’t have bars. They will install it only next week. Get out.

My legs are trembling. The first attempt to climb onto the windowsill fails. The man, apparently still in shock, rises slowly. Desperately, I gather my strength and jump.

Children playing in the yard shy away in fear. My left ankle landed unsuccessfully. Pain. Horror for a few seconds gives way to excruciating anxiety — has anyone noticed? I wave to the children with my hand — everything is fine, this is such a game — and limping, I run to the bus stop.

Twelve years until the death of this man, I came up with all sorts of excuses so as not to go to him during family visits. I will never see him again, not even at his funeral, but for all these years, the fear of accidentally stumbling upon him will always follow me.

Why did I just stand and smile like a sheep? Why didn’t I leave the moment I realized something was wrong?

Why? Because for well-behaved girls and boys, an adult is an indisputable authority. The defender who punishes you only if you did wrong. The meaning of “bad” and “good” is also decided by an adult. Because he is not a villain from a book, but a close person. The thought that a loved one may feel something shameful towards you is so terrifying that you dismiss it hastily.

Because in the society that encourages hypocrisy, we are not used to living our feelings and desires, and even more so to declaring them. We make excuses and justify ourselves. And we feel awkward — instead of just saying “I don’t like it” or “I don’t want to”.

Because girls and even adult women are often afraid of expressing disagreement with someone’s bodily or verbal creeps, to stumble upon the mocking “Are you so full of yourself?” and “You’re mistaken”.

And often you can’t prove it. You can, of course, say: “Even if you have nothing bad in mind, I don’t like how you look at me / touch me / talk to me. Stop it”. Without further explanation. I just don’t like it.

I got to know all that only when I was thirty years old.

I will manage

I’m eighteen years old. A strange teacher of an incomprehensible subject asks for help to take the papers to his office after the exam and sit with him for a bit. He has a tired face. He closes the door. I sit on a chair — in a strict brown skirt and white blouse. He sits down beside me. He looks at me and smiles. I feel uneasy. This desire appears again — to leave immediately. But I squeeze my hands and smile timidly. I am still a stupid naive girl with great faith in humanity. I still can’t say no.

“I heard you draw,” he says. “Draw me something.”

With a trembling hand, without thinking, I outline an embryo. I often painted embryos back then. In a curled up, self-defending posture. The teacher looks at me in amazement. He did not expect such a picture. And suddenly he squeezes my face between his palms and begins to kiss it. He asks me not to break free. With excitement in his voice, he says how lonely he is and that he doesn’t have anyone around him. And that I have is a beautiful body.

I start punching him quickly so that he doesn’t have time to recover. He is trying to grab my hands. I sweep away a pile of books and an electric coffee maker from the table, and again the horror of what is happening gives way to an alarming thought: has anyone heard the uproar? I will break free from him myself, I know now that I am strong. People, just don’t come here and don’t make a scene out of it.

Either from the machine-gun fire of my strikes or out of surprise, the man loosens his grip. I break out and run to the door, get out into the corridor and run. When I get home, I try to wash off vile sensations from my face, like they do in horror movies. I don’t know about movies, but in reality, it doesn’t help much.

In my head, paralyzed with disgust, only one thought is ticking: summer, vacation, and then another year to spend with him.

After that, for two semesters I tried not to go to his lessons, and if it didn’t work out, I just sat there like a wooden doll, unmoving and dull. He treated me the same way as others, not showing that anything had changed at all. Only once he caught my hand on the landing with nobody around and asked why wasn’t I attending his lessons, and whether he offended me somehow.

I broke free without answering. After that incident, I became uncomfortable using elevators, stairs, and being inside rooms with doors closed.

My hatred towards my body that’s able to push people only to “this kind of thoughts” is intensifying. Every summer is a nightmare. I hide my body in wide trousers and spacious T-shirts. My male friends don’t understand why I began to shy away from them. Even a casual and fleeting touch of someone else’s body becomes torment. The embrace of even the closest people — as a fulfillment of a painful duty. The only relief is to push my soul out of the body, sending it on a journey. So that it exists separately.

Only one man whom I have known for many years and who is an older, much older friend, I continue to trust. He is the only person who I really want to tell about what happened to me and to hear that I shouldn’t blame myself.

I am sitting on the couch, listening to another story from his adventurous life and thinking that, perhaps, the world is not all shit, and that I can handle it.

A few years after that, he locks me in one of the rooms and says that he has always liked me and that I am very “interesting”, both as a person and as a woman. It’s okay that he is married, that his wife is also dear to me, and that occasional flirting with me will only strengthen the marriage by pouring fresh colours into it. That I have a beautiful body, and he thought about it from our first meeting. And I thought with horror that at the time of our first meeting I was only ten years old.

These years flashback in my memory in reverse order with the speed of lightning. Like in movies again, when the hero falls down from a high rooftop, and life flashes before his eyes. All our communication, talks and touches — I remembered everything in the smallest detail. I was so blind, wasn’t I.

I want to smash this Humbert Humbert’s head onto the electric stove where he’s warming his hands as he tells the story, but the impulse lasts only several seconds. Fatigue comes after it, and I don’t care anymore. I want to get out of here, disappear, fall asleep, and wake up with different memories. Halfway through the story I stop him, get up, slowly put on my jacket, take my backpack, and demand to open the door with a calm voice.

Just as calmly I say that I won’t tell his wife and anyone else about this, I will say “Barev” if we meet in public, but he will not dare to bother me. My indifferent and calm voice creates a stronger impact than tears and screams. He silently opens the door.

I get in the car and drive along the night streets for a long time. Through fatigue, joy emerges. I haven’t frozen in place, weighed down by chains of imposed behaviour. I haven’t smiled stupidly because he was “a family friend”, or because “I misunderstood”. I haven’t pretended that I didn’t hear anything, and didn’t try to wrap it up as a joke. I stood up and left.

I’m not a little girl anymore. I can now say “no” and “I don’t like this”. Without a reason or explanation. I know how to turn around and leave. Do I still have traumas?

Yes. In the form of phobias, which I have to constantly work on. For example, I still sleep with the lights on. It can be frightening to be indoors or walking alone along unlit streets. It is scary when I walk along the sidewalk, and a car slowly drives along the street. Even if the driver is clearly looking for a place to park, I start to panic.

I will scan your house as soon as I enter it. Even if you are a 14-year-old girl, alone at home. I check windows for the presence of a grill, remember which of the three locks you used to lock the door. I don’t live in constant tension, though. I do all this instantly, for the most part unconsciously, according to a habit developed over the years, even before I can stop myself. But there are victories, too: for example, I stopped putting sharp-cutting objects in my pockets, bags, and car doors.

It’s not your fault

A few years ago, I started working with horses in the village of Ushi (30 kilometers from Yerevan). For the first time, I went to the village on the last day of July during the extreme summer heat. I was wearing a T-shirt and shorts. It was a fifteen minutes walk from the bus stop to the stables.

In the gazebo at the bus stop, men played cards for money. Near the shop, others drank beer and smoked. In the courtyard of a large two-story house, firewood was sluggishly sawn for the winter.

Suddenly silence reigned over the village. Everyone abandoned their affairs and stared at me in amazement.

A month later, those rare women who treated me well advised me to come to the village in more conservative clothes.

“Only prostitutes dress in shorts.”

“We know that you are a good girl, but you should consider men as animals. Their main organ of thought is not in the head at all, and your shorts will only push them for one thing.”

“You can’t possibly accuse a man of his desires and actions when you stride in front of his eyes like this? You should have taken alcohol in your hands, too!”

It turned out that generally, the only way to get raped is to be a drunk whore in a miniskirt.

This is the way we defend ourselves by blaming the woman’s appearance and behaviour. If we are “good” and “right,” and nothing will happen to us.

There is no such magic wand or spell by which all the “maniacs” will become saints or disappear from the face of the earth. There is no woman who would be safe from being in the wrong place at the wrong time, regardless of her intellectual, social level, or behaviour.

Only the rapist carries the blame for the violence. When choosing a victim, they are guided not by its attractiveness or level of emancipation, but by the possibility to remain unpunished.

The best defense for the rapist is the silence of the victim. The irreparable damage may not happen if parents teach their little daughters to speak with them on any, even most sensitive issues. They must know that they will be believed and trusted and that their parents will do all the right things. They must never ever be faced with a question like this one: “Why did this happen to you?” Because the real answer to this is our silence.

I can imagine how scary it is to hear from your child that he was being harassed. Even more so if it wasn’t some psycho from the streets, but a person whom you know very well. It is scary to accept it and to act. You might want to stick your head in the sand and pretend to be deaf.

It will be difficult, but a child won’t stand a chance in such a situation without your protection and trust.

It would be great if parents could resort to the help of a professional child psychologist. But, unfortunately, in Armenia, there is no specialist working with the little victims of sexual harassment.

It would be great if people from a young age learned to set boundaries, to trust their feelings, so they wouldn’t have to come up with words and excuses to justify their “no.” I just don’t like it. I don’t want it.

Become a Patron

We are building a community of affectionate, non-judgemental people with an open mind. If you want to support our work of investigating the deepest social issues through personal stories of real people, the best way is to join us and become a Patron.

Text is over, story goes on

Here on Kalemon, we bring unspoken social issues to life in the form of narrative stories. Our mission is to create social impact by breaking taboos and freely discussing important matters, such as violence, poverty, discrimination, parental and medical ethics, and so on.

Kalemon is a non-profit online media that exists thanks to the financial support of individual people. Small, but regular donations from our readers help us write articles, train & recruit new authors, maintain and develop the website.

As little as 2 dollars per month can make a difference. Thank you!

Станьте Патроном

Мы создаём сообщество неравнодушных, свободных и непредвзятых людей. Если вы хотите поддержать нашу работу по разбору глубоких социальных проблем при помощи личных историй простых людей, самый лучший способ это сделать — стать нашим Патроном.

Текст закончен, история продолжается

Наша миссия — способствовать изменениям в обществе, ломая табу и свободно обсуждая такие важные темы, как насилие, бедность, дискриминация, родительская и врачебная этика — и так далее.

Рассказанные здесь истории всегда будут оставаться честными и непредвзятыми — в том числе благодаря нашим Патронам. Вы тоже можете присоединиться, нажав на кнопку и выбрав размер поддержки.

Каждая подписка, начиная от 2 долларов ежемесячно, поможет авторам создавать новые материалы. Спасибо!