Even punishment should include care for a person

Author: Hasmik Hovhannisyan

Editor: Fëdor Kornienko

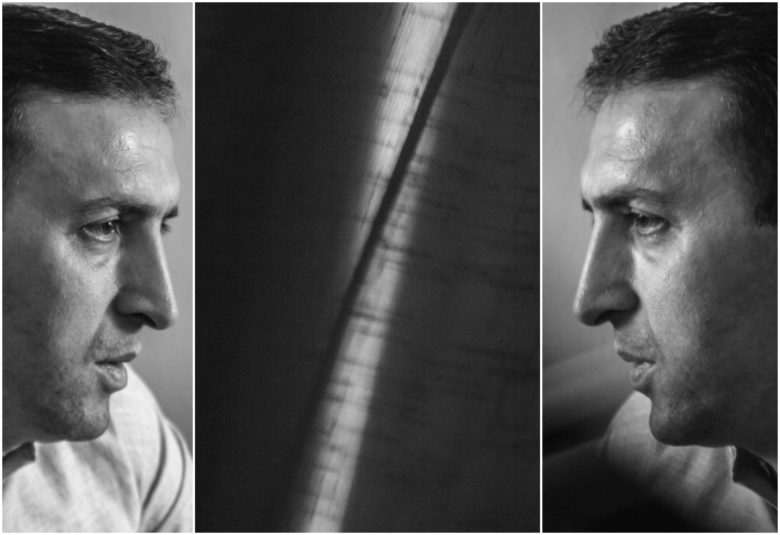

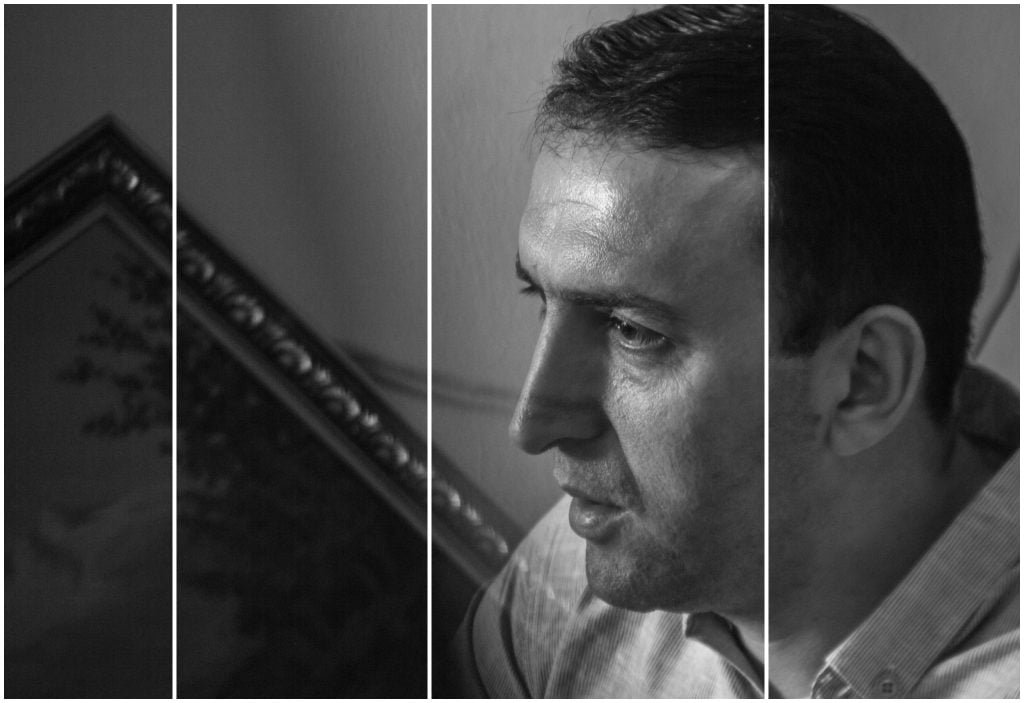

Photography: Fëdor Kornienko

Author: Hasmik Hovhannisyan

Editor: Fëdor Kornienko

Photography: Fëdor Kornienko

“If we are against the fact that a criminal should receive education and proper rehabilitation at the expense of the society, then he will just stay in jail at our expense, and sometimes stay repeatedly. We will pay that money anyway. The question is what we will get as an output.”

25 min read

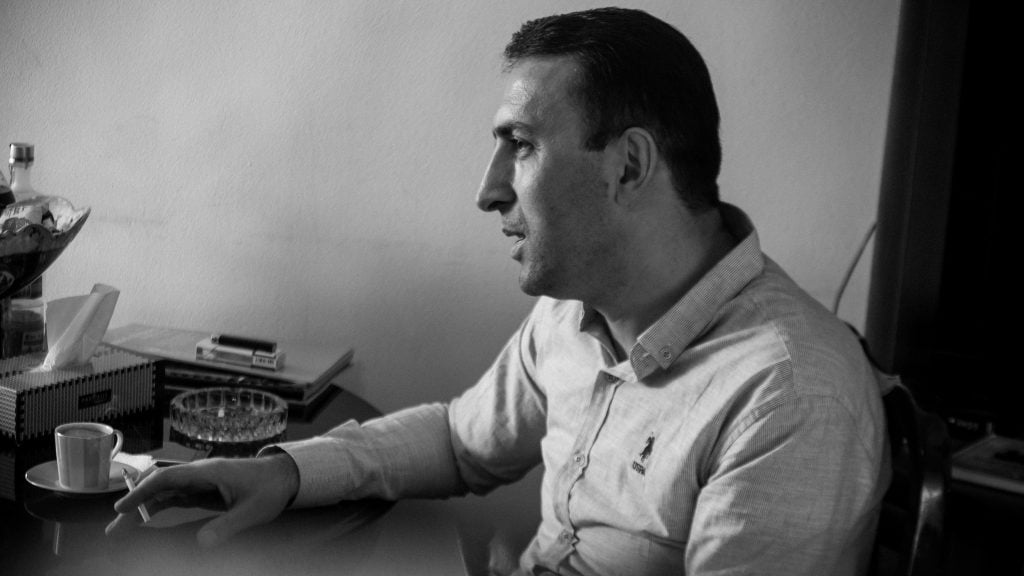

So says a former life prisoner Ashot Manukyan. On January 24, 2020, he was released directly from the courtroom of the Criminal Court of Appeal and became the second life prisoner in the history of Armenia to receive parole not for health reasons, but thanks to his positive behaviour in prison for 24 years.

While still in prison, Ashot entered the University and is now in his third year at the Department of Psychology. He wrote two books: the first is a confession in the form of a monologue addressed to the soldiers in a friendly manner; the second is a collection of poems dedicated to the April War.

We talked to Ashot about how much our punishment system actually contributes to correction — and whether it now sets such a goal; why is it important to have a human attitude towards a person, even if he has committed a crime; how education can help reduce recidivism statistics among convicts; and also about the accompaniment by the Probation Service of a released prisoner and the need for reform of the penitentiary system.

The article was created in partnership and with support from the Council of Europe, Armenia.

Whoever was weaker was going to swing

— How did you feel about the “criminal” concept when you were eighteen or twenty years old?

— I am from Akunk village, Vardenis. We had regional authorities, and I was close to the criminal circle of Vardenis. Some of my friends were regularly released from prison, and some were taken away. And my cousin-uncle worked in the police. I was close to these and those. My lawyer asked both criminals and the correctional officers about me. And he said: “Ashot, I have never seen a person like you in my life. And here they love you, and there. Whose side are you on?” And I replied, “I am neutral; I am in harmony with all” [laughs].

— What were you like when you were drafted? What was your character?

— Nasty. Although, what I call nasty… most guys of my age had such a character – hot-tempered, quarrelsome. Among my friends, probably 90% were like that. It is such a transitional age — the time of self-realization, suppression of each other, achievement of everything by force, through fights. Society assigns you this role of “normal man”, and you start performing it. Whether you play well or badly depends upon you.

— But at the age of seventeen, you don’t realize it’s an imposed role.

— No, you have no alternative. For example, according to statistics, 85% of prisoners in Armenia return to jail. About 5-10% may be committing a double crime deliberately, but the rest, I’m sure, does that unconsciously. They get out of prison resentful and embittered at society. Conditions of detention, attitude — everything tells a person: you have committed a crime, you are a scoundrel and you will remain like that. Under pressure (of public opinion), he accepts this role and gets used to it.

It was the same at seventeen or eighteen. We corresponded to society’s perception of us. Someone beat someone, protected his truth by force — he was great. Who was weaker — went to swing.

— Did you want to join the Army?

— I was a teenager when the backbone of the [Karabakh] liberation movement was formed in the village of Pambak in Vardenis. In the tenth grade, I often missed lessons, even missed exams. I met Leonid Azgaldyan, Monte, went to Karvachar, and talked with the guys from the [Monte Melkonyan] detachment. Like many of my friends, I was captured by the movement, of course, and we were also eager to go to the front.

I really wanted to go to the army. I had options to go away with it, like giving a bribe, as it was done then, there were influential relatives, or at least to go to Yerevan, to an excellent military unit, but I didn’t even consider it. I said — I’ll get where I get. My two younger brothers also served after me. Relatives advised our parents to release them from the army and take them abroad, but they did not agree.

— And where did you end up?

— To the city air defence unit in Artik. I served there for nine months, and then spent five months in Mataghis. In December I was transferred to Krasnoselsk for two months, from there — again to Artik. A total of a year and four months were served when that incident happened.

Ashot says either “that incident” or “my crime,” when he speaks about the reason for which he was sentenced to death, which then changed to life imprisonment. His face immediately changes as if it freezes. I am trying not to ask too many questions. He has already described that in his booklet.

In the winter of 1996, the ordinary soldier Ashot Manukyan visited a friend from his former military unit near the village Tufashen. A dispute broke out between him and his friend, who owed him money. Twin brothers that were serving together with his friend interfered in it. The dispute continued the next morning near the Pemzashen area, a base where anti-aircraft missiles were guarded. It developed into a fight between Ashot and three guys. Ashot grabbed the AKM, stored in the room, and opened fire.

The bodies of three soldiers were found only the next day. Ashot himself was found in Yerevan three days later. He confessed to the crime and also showed the storage location of three AKMs assigned to the killed soldiers. The duty officer was absent from the security post, as well as the fourth soldier, who was also supposed to be on duty that day.

— How did you move so freely from one military unit to another?

I warned the deputy commander of the battalion that I would be absent for ten days. During the roll-call, he was not calling out my name. My uncle was one of the guys who fought [in Karabakh], and then the military mostly consisted of them. I served in Krasnoselsk, all the regiment commanders knew my uncle, and I never had any problems. I then left home every Friday and came back on Monday. I washed, walked, and came back.

But if the officer on duty had been in place [at the base], the crime would not have happened. I don’t want to justify myself in any case. Yes, I have committed a crime, and I had to serve my sentence. But we had fifteen lifers [in war crimes], and now there are fourteen. If we study their individual cases, we will find officer negligence in one way or another. But in all cases, only soldiers were punished.

Even if punished for negligence in their official duties, officers were either given conditional punishments or were temporarily suspended from their job. There was a boy with me in prison, Zakar. He was jailed because he used to keep and beat a fellow serviceman in a military depot (kaptjorka) for one week. A nineteen-year-old hot-tempered boy — yes, he was guilty. But where were the officers? Didn’t anyone notice that the soldier was absent during the roll-call for one week? There, first of all, all the officers should have been put to jail and then Zakar.

Now it is strict [in the army]: If a soldier does not turn up during the roll-call, they immediately notify the military police.

— And why didn’t the soldier who was beaten by Zakar complain to the officers? Is my question naive?

— Soldiers do not complain to officers. The mindset of “a good guy doesn’t complain” is at work here. Besides, there is no precise mechanism that an officer would be guided by. A soldier went and complained of another soldier. The latter was detained for five days in a guardhouse. The term expired, and he returned. Is the person who complained protected? No. While the first one is serving his time, his friends can push the other [the one who complained] to commit suicide or even kill him. The street culture that has infiltrated the army, and fear, these keep the soldiers away from complaining.

— That culture also sneaked into the prison.

— Naturally.

You will all be killed

— Do you remember the first day in prison?

— I do very well. For the first four or five days, I was kept in the military police, then for fifteen days in the garrison. From there, I was taken to “Nubarashen” [penitentiary institution]. I was taken to a place called a “box” and left there for a few hours. There is nothing there, even no place to sit. Nowadays, one or two steel plates are attached to the wall in one or two boxes. There is a small brick-sized window on the wall. I thought that’s the cell, and I thought in horror, “How am I going to live here?” Then they took me, took my fingerprints, and escorted me to the actual cell.

There were three iron beds — you know, with springs, and on them a thin mattress that pierced into your body. It was better to sleep on the floor. There was also a small iron table nailed into the ground and backless benches on either side of the table so that two people could sit.

In “Nubarashen” — and all death row prisoners were held there — there were five cells for those sentenced to death. Until 2000, in each cell, it happened, there were six or seven people, then five more cells were added, and there were three or four people in each.

Now lifers are kept in these cells — the beds were set to normal, the toilet in the cell is now closed — in my time it was open. They have made the windows bigger. Then there was a narrow gap, with four layers of netting and metal bars, through which it was possible to look only up at the sky. We almost used to guess what time of day it was. The lights were on all night. It is a form of psychological pressure. A guard walked in the corridor and looked through the peephole into the cell every twenty-thirty minutes. During the last years, when I started to study psychology, I understood how badly the constant light affects the person. I was secretly breaking the lamp. One needs to sleep in the dark.

— You spent seven years in such a cell. I try to imagine what it means to think every day for seven years that this day may be the last.

— Those were painful and cruel days. There were rumours about an unwritten order of Leon Ter-Petrosyan [the first president of Armenia] not to carry out the death penalty. When the guards wanted to oppress or punish us for bad behaviour psychologically, they said: “The order will not be valid starting from the next month, you all will all be killed.” And no one knew if it was true or not.

—How did you communicate with the outside world and each other?

— Communication with the outside world was not allowed. Visits and home deliveries were prohibited. They didn’t even take us for a walk. We used to communicate from cell to cell, but we didn’t see each other. We were only taken to the bathroom every six months to take a bath. They were taking us from the fifth floor to the second floor. However, that was mostly a formality. “They are scoundrels sentenced to death. They don’t need to bathe or even to eat. The sooner they die the better.” This was the attitude of guards towards us.

We were given eight half-litre bottles of water for three or four people a day. There was a faucet in the cell, and they turned on the water from 7 to 10 and from 18 to 21. We used to break a razor, screw wires to two razor blades, and make a boiler. We heated the water and washed ourselves like that.

A human being adapts to any conditions. When it seems that there is no hope, you would think one should sit tight and wait for death, but no, washing the body is still relevant.

Each person received one “loaf” of bread, millet, and pickled cabbage. During the first twenty-three years of [my imprisonment], prison food consisted of grain and cabbage every day. In two or three [correctional] institutions, food has changed since last year, and now the food is supplied by a private company and is similar to the one we eat in freedom. They bring four types of food, and one chooses. The prison staff said that the food, which is much better than the previous one, nevertheless enabled them to save 200,000 drams per month. Can you imagine how much they used to steal back then?

The bread was then with a hard crust, and inside was raw dough… like a liquid. We only ate the crust, it was impossible to eat the crumb. If angry, the correctional officer would cut off the top layer and give us the crumb only.

— Did anyone die because of that food only?

— If my memory serves me right, about thirty people have died in seven years, from food and beating. If the verdict was the death penalty, the guards could enter [the cell] and beat even if the person hadn’t done anything.

— Did they beat you?

— Very few times. I was lucky. I had relatives and friends both in the law enforcement and prison system, which did not allow me to be beaten. And those who did not have such acquaintances had miserable fate. [The guards] could enter the cell and hit me lightly on the shoulder, allegedly pulling me aside, and beat the others. And you cannot defend them anyway, because you will also get it. I tried to interfere several times and was beaten up.

— And if people died because of the beating, what did they tell to the relatives?

— Various diseases. They didn’t die right away. Some two months after the beating, for example, there were problems with the internal organs.

— How can one not get crazy in such conditions?

— There were people who went crazy. We still have prisoners who are in a state of insanity and are in prison. They get psychedelic drugs there. Keeping them there, I think, is inhuman. They must be in a psychiatric clinic.

Invented another reality

— I read in your booklet that you never thought about suicide. I didn’t believe it.

— Yes, that’s not entirely true. I thought a couple of times very seriously. But it never came to action.

— What was stopping you?

— Thinking about parents, first of all. I thought a lot, talked to myself — am I really so weak that I can’t stand it? I have so many things to do. I thought that I needed to earn the forgiveness of the injured party…

… and suicide wouldn’t be the best way?

— Yes.

The parents of the killed soldiers forgave Ashot and petitioned for his parole.

— How did you manage to get the forgiveness of the soldiers’ parents?

— It took years. All the time, while in jail, I was dreaming of speaking to them.

As soon as I got a phone, I called. I didn’t start talking to them immediately but spoke with relatives, neighbours, common acquaintances. My parents did meet them. My lawyer went to them, and the mother of the twin brothers told my lawyer, “Just as I didn’t meet my sons from the Army, Ashot’s mother didn’t meet up with her son. But as he is still alive, I would like at least her to meet her son.”

— And were there any people sitting with you who committed suicide?

— Yes, not from my cell, but I remember a few cases from neighbouring ones. There was a small hole in the top of the toilet, a window with bars on it. It was not clear why they put bars there; only the hand could be inserted, as if those were made explicitly for hanging. That’s where they hung themselves.

— Four men are locked together in a small room for years. What are they doing all day?

— Most of them used to make something from the inedible part of the bread. They even made khachkars (cross-stones.) They could work on one khachkar for a whole month, from morning to night, working on the details. Then they gave it for example to a prison officer for a pack of cigarettes.

I used to read. I wrote projects, for example, about agricultural development cattle breeding. I threw away 80% of what I wrote. I knew it was stupid.

— Did you write this when you were in the cell, from where you could be taken to death every day?

— Yes, I perhaps invented a different reality for myself so that I could somehow break away from the one I was in. I think I did it subconsciously. Only then, when I began to study psychology, was I able to analyse what I was doing and why.

I read a lot during the first seven years. Books saved me. I’ve loved reading since I was a child. My grandfather had a large library, and he gave me books from there.

Books saved me.

Nothing was allowed in death row, including books brought from home. The guard used to bring some books from the prison library of his choice, if you don’t want to, don’t read.

—And what books were in the prison library?

— There were a few hundred old Soviet books, for example, many books about the Patriotic War, nothing exciting. Armenian and Russian, then English books appeared from the “Red Cross” (by the end of 1990, the Red Cross employees were provided the right to visit the prisons — Kalemon). There were also Iranian books in “Armavir,” provided by the Embassy.

After a while, they started to hand me the books sent from home secretly. Some employees were bringing books as if for them and giving those to me during the night and getting them back in the morning again. There were cases when they forgot to take the books, and the books stayed with me.

One day the guards found my books and started kicking them out of the cell. I remember it very well. It was very painful to watch them kick the books out.

— Was there any book that you were impressed with and wanted to be like its hero?

— There were no heroes. But The Golden Man (a novel by Hungarian writer Mora Jokai — Kalemon) was very impressive — a wonderful book. I read it back in death row my grandfather sent it to me. The hero, his actions, had a very strong effect.

— Can one get used to prison?

— One adapts to any conditions. It would be an exaggeration to say that one does not think about freedom. But a person has a very strong ability to self-deception and the ability to adapt to any conditions.

That is why, after seven years, the punishment is meaningless, because after seven years a person feels himself completely a part of this environment. He no longer perceives isolation, the lack of space as a punishment, does not feel the pain of separation from relatives. What then is the meaning of punishment?

— So, it seems one becomes kind of dull after seven years?

— Yes, when I was released, the next day I went to the village and I went to the grave of my grandparents. We were very close especially with my grandfather. I was his first and favourite grandson. I must have sat there for an hour and cried in anguish. I was just choking. I felt the same yearning for the first seven years. And the other seventeen years I was kind of … cold. As if the organ responsible for the senses had not worked all those years, but now it has suddenly revived.

Drink borscht water and you’ll be alright

Armenia became a full member of the Council of Europe on January 25, 2001. In line with Article 13 of the National Assembly Conclusion № 221 (2000), it undertook the commitment to adopt the second (special) part of the Criminal Code, through which is de-jure abolished the Death penalty.

In 2003, the new Criminal Code of Armenia was adopted, according to which the death penalty was abolished and replaced by life imprisonment. The Council of Europe has declared the abolition of the death penalty one of its top priorities. For many years, the organization has struggled to ensure that the death penalty throughout Europe loses its legal force and that its renunciation becomes universally recognized. As a result, no executions have taken place in the member states of the Council since 1997.

Protocol № 6 to the European Convention on Human Rights abolishes the death penalty in peacetime. It came into force on March 1, 1985. Europe’s position regarding the legalized murder has shifted from permitting to banning in line with the Protocol № 6. Protocol № 13 that came into force starting July 1, 2003, prohibits the death penalty, regardless of the circumstances, including crimes committed during the war and the imminent threat of war.

— In 2003, the death penalty was abolished, and you were transferred to a lifers’ cell. Did the conditions improve?

— From 2003, wooden beds were placed in the cells, and cabinets were allowed. Before that, there was a cabinet in “Armavir,” but not in “Nubarashen.” There was something made of iron, and the inmates called it “ghshabun” (a pigeon nest), which was comprised of some small cages where the plates could be put.

“Armavir” is more or less furnished, but there are problems there as well. The most important is the problem of ventilation. There was no ventilation system there. There was a small window, but once could not open it in the winter, as it was cold. And the heat was terrible in summer. In “Armavir,” buildings are located opposite each other. So, each cell is closed on all sides. In “Nubarashen,” they opened a peephole on the door, and together with the open window, at least some kind of airflow was created, but in “Armavir” this was not the case. Now, I think, they are going to resolve this issue.

Back in 2003, when I was transferred to a cell for lifers, I was allowed to have a refrigerator. We kept the food sent from home in it. It was common in “my” cells, everyone shared. Sooner or later, we would get a lot of diseases just because of prison food.

— By the way, about diseases. What was the situation in the prison healthcare system? How were you treated?

— Improvements have been seen in the system since 2003, thanks to international organizations such as the Red Cross, the Council of Europe and the Human Rights Defender. Prisoners began to be transported to civilian hospitals for treatment.

In 2003-2004, the dental room was quite well furnished, but I personally didn’t like the dentist, to be honest. I had a dentist friend. If I had dental problems, I would call him, and he would come.

Before that, we had a clinic where, unfortunately, only methadone was distributed as a treatment to those who was hooked to it.

When someone needed a doctor, the latter was asking the reason for being jailed. If he “didn’t like” the crime, he would tell, “Drink borscht water, and it will pass.” He called borscht the pickled cabbage (sauerkraut) and the pieces of potato and carrot floating in the water, which we were eating every day.

A couple of times it happened when someone had appendicitis cut out. They used to operate in a regular city hospital and bring the people back immediately with the wounds, which inflamed. It was a miracle that people survived; the instinct for self-preservation was very strong.

When I was still in the death row, if someone had a toothache and the tooth needed to be pulled out, they kept them with cheeks swollen for a few days to suffer a little more. Then they took them to a dental room, which, together with its butcher-dentist, looked more like a torture cell, and removed the tooth without anaesthesia.

— Were there any lawyers visiting you then? Did you complain to them, or were you afraid?

— Let’s say we complained. Where would our complaints go? Who cared about us? Then, as a result of international organizations entering prisons, the situation improved. Writing letters was allowed. The “Red Cross” employees were passing our messages. They had particular forms, on which we used to write. At first, there was such censorship! It happened that you received a letter from home, and some of it was deleted so that the meaning would be incomprehensible. What kind of forbidden things could the relatives write about? They were just nasty.

— You have an open mind, a literary language, and a bunch of plans. You break the stereotypes prevailing in society about a person who spent 24 years in a closed world with its own strict rules. Is the fact that you have maintained your mental health and your mind’s clarity only your merit, or is it due to the system called to correct it?

— I’ve worked hard to avoid temptations, such as drugs or gambling, which are very common in prison. Also, I was lucky to have met such people, as … I got in touch with Armenak Mnjoyan (“Dro case” lifer who passed away in hospital in 2019 — Kalemon), let him rest in peace, Arsen Artsruni (“Dro case” lifer), young guys, who were inspired by me and I was inspired by them.

And the system … it has always been and remains divided into two parts. There are employees in prison, even graduate psychologists, who think that a person can change, and there are also those who believe that he cannot, and they should not work with him. Unfortunately, the latter are the majority.

There were employees in the prison who helped me. For example, in 2009-2010, when we were allowed to get a higher education, I was asked where I wanted to go. I wanted to apply to the Gladzor University Administration and Management Department but was weak in math. One of the social psychologists started to teach me during his working hours and even during breaks. And in “Nubarashen”, “Armavir,” “Sevan,” where I spent only two months, there were other employees who tutored the problematic subjects to me for hours.

But there were also other guards. For example, when my friend Arsen Artsruni was teaching me English, and we were staying in different cells, Arsen was writing down the tasks. I was completing those and sending them back to him with the help of the prison staff. They had to take those papers a few meters only, but the papers were always “getting lost.” They had such a communist mentality that the person who committed the crime is a scoundrel, no matter what he does.

They looked at the criminals as the dregs of society who would not be corrected. Why should he develop, gain knowledge?

Die first, then be free

— Nevertheless, you managed to get into University.

— In 2011, I applied to Gladzor. But they demanded a bribe from me, and I refused. Then I tried to apply to “Yerevan Mesrop Mashtots University” and Yerevan State University (YSU), but the Faculty of History this time. I loved history very much and knew it well.

In “Mashtots,” they honestly said, “we are sorry, but we won’t go to prison, there is no desire for it.” And in the YSU Rector’s office — I think I talked to the vice-rector — they told me, “Boy, what are you talking about? Do you at least understand where you called?” I replied that I had the constitutional right to study remotely at any HEI and that I will study, write papers, and they are obliged to provide conditions for me, in particular, to send the lecturers to prison to examine me. We already had a computer, but there was no Internet.

The YSU also refused, while Arsen was already studying for a Master’s degree at Urartu University. The rector of the University, Professor Sedrak Sedrakyan, willingly agreed [to accept me]. I am already in the third year of “Pedagogy and Psychology.” I study on a paid basis. Now, as I am already out, I shifted to day-time studies. When I was still in prison, one lifer also applied to “Urartu,” after my release, three of them applied too.

— When you were getting an education and reading, did you think that one day you will get out? Did you prepare yourself to live in the “free world?”

— No. There were people sitting with me in prison who had been sentenced to life for one murder or even complicity. I saw that such people were not released, and I thought that I would not be released. But I didn’t know that they would stay and I would leave.

I always thought that I needed education in prison because when you are educated, you even write a simple application competently.

This happened when I was in “Sevan.” Someone was given juice from home, put behind a “tumbochka” (side-table), and forgot. The guards found it and wrote that they had found a “self-made brew.” They filed a case and were going to incarcerate him for a week. He told me this in despair, and I told him, “go and explain to the guard that they sent you juice from home, and it went sour. How could you have made it yourself? Out of what?”

He went and told them. The head of the shift said, “Ashot taught you that” (laughs). That is why the basic knowledge is needed. Otherwise, the prisoners do not know their rights, and they obey out of fear. And the prison staff has to show their bosses, “Oh, I worked, I found a disorder.”

But each such punishment puts off the possibility to parole for six months.

— How effective is the system of sanctions and encouragements used in prisons? What were you punished for?

— I was punished for five times only, all in 2008-2014 and all because of having a phone. They were not allowed, still are not allowed, but there were even more of them than there were chocolate in prison.

That was the time (2008 — Kalemon) when I wanted very much to speak to the injured party, and wanted to get their forgiveness.

I also wanted to keep in touch with my parents. After March 1, my parents had to leave Armenia. (On the night of March 1-2, 2008, as a result of the clash between the police and the citizens led by the first President of Armenia Levon Ter-Petrosyan that were complaining of the falsification of elections, ten people were killed, and more than 200 people were wounded – Kalemon.) My brother had taken part in the demonstrations and was injured and sought [by the law enforcement bodies,] and my parents took him out of the country.

Since 2014, I had been trying very hard to avoid any penalties. I tried not to keep a phone on me. I consider the legalization of phones in prison very important. Let the prisoner pay 5,000 drams a month for a regular telephone and 10,000 drams for a good internet-connected phone. And that money can be used to educate prisoners.

— And what else are there sanctions for?

— Fights, swearing, disrupting the order.

Employees are also fined for swearing and even fired. This depends upon the prison chief. There are such prison heads that are strict and demand that employees treat the prisoners following the law. Some swear and set a bad example.

— And in what cases are encouragements given?

— I had two — for exemplary behaviour and for participating in the cell repairs — painted the wall. But in recent years, the Prosecutor’s Office has strictly banned encouragements. My behaviour did not change, and on the contrary, I also published a booklet for the army, a collection of poems dedicated to the April war. I entered the University, and I study very well. The University petitioned for encouragement. But they did not encourage, they said there weren’t enough grounds.

Our law on incentives is not clear. For example, Arsen and I have researched, that in Italy, when a prisoner takes a book from the library and hands it back, the librarian asks him questions to understand if he really read the book. If yes, then three days are taken out of his term. If a prisoner enters a University, six months are taken out of the term. When the prisoner transfers to the second year, three more months are taken out, graduated — another six months.

While in our country, they only write on paper “have incentives,” and that is it. The only use of that encouragement is that when one applies for parole, they refer to it. Five points are credited to your account by the credit system for more than two incentives. It’s the same if you have two or five. I think it is stupid.

— And why did the Prosecutor’s Office not welcome “encouragements”?

— The Prosecutor’s Office does not appeal against one out of a hundred cases of the parole applications. If the prisoner has the encouragement, the court takes that into account, making it more difficult for the prosecution to appeal. Our Prosecutor’s Office has remained in the old way of working. It just wants to punish, and that’s it. First, it forbids the encouragement. Then it tells, no parole, for example, you have not got any encouragement for the last three years. Even if the person is sentenced to imprisonment for a few years, and has behaved well, the Prosecutor’s Office believes that he/she shall serve a sentence until the last day.

After twenty-year imprisonment, I was not introduced to parole. According to the law, they were required to do so. I appealed against that to the court. After the court session [during which I was rejected], the young prosecutor approached me. “What freedom for a life prisoner? Your freedom is death. When you die, you will be free.”

Care in punishment

— Have you met criminals whom you yourself “sentenced” to death for their crimes?

— Yes, there were such cases, but those were only moments, I did not let them last. I said to myself: who am I, what right do I have to judge him?

Perhaps all of us would get angry when seeing a person who had committed a grave crime. However, a person that represents the state does not have a right to get angry. That person has precise functions. That person shall forget his feelings and perform his duties.

It is clear that the person who committed a crime must be punished. But even in punishment, there must be a concern for a person. Isolation from society, from family, and friends is already hard in itself.

If a person self-corrects and acts in a way that should be encouraged, and the Prosecutor’s Office doesn’t do that, I think they commit a crime, meaninglessly keeping him in prison at the expense of society.

Our [prison] system is not very efficient and needs to be reformed. OK, let’s put to jail and isolate the person from the public for severe crimes. But there was a person jailed with us for stealing six skewers, which he even didn’t steal. He was drunk and climbed drunken over the neighbour’s wall, took the skewers from the garden barbeque place, made the barbeque, and put the skewers back later.

A rich neighbour did not like him because of his drinking. He was very hardworking, he made tombstones, but he was also a drunkard. And then the neighbour took the opportunity and called the police. He was sentenced to six years in prison. Can you imagine six skewers? He is still in jail.

Another case. Six Pakistanis were in prison. Because I know English, I used to communicate with them. They said in Turkey that they wanted to go to Germany. Near our border. The Kurds there perhaps understood “Ermeni” and pointed to the border. The latter passed the border and were arrested. Each of them was sentenced to three years in prison for illegally crossing the border. Calculate that 180 000 AMD was being spent on each of them, multiplying it with three years, millions. Why not put them on the plane and send them back home?

And I have seen so many people like this during twenty-four years that are in prison for senseless crimes and senseless terms. I always had a question. Well, our Government has been feeding these people for years, spending so much money in vain, and in those conditions, so many lives are being ruined. And we feed them at the expense of our elders, children, soldiers, on whom we could spend that money.

— What happened to the Pakistanis?

— They served their sentence until the end and got released. Two of them were wandering in the city being hungry, have reached to Norq, stole phones from two girls, and ran away. They were caught and sentenced to five years in prison and sent back to jail.

— True, absurd, about keeping the prisoners. Many people are outraged when they hear that at the expense of their taxes it is necessary to improve the conditions of detention of prisoners, or those prisoners should be treated with respect. Why should the public be interested in caring attitude to and normal conditions of prisoners?

— And what shall we do with them? Shall we burn them all?

— Well, let’s keep the minimum conditions, and that’s it.

— Once I refused to go to the next court session from “Sevan.” In the next session, I was asked why I did not show up, and I replied that I did not want to go through those humiliating conditions. They used to bring me to “Nubarashen” some seven-ten days before the hearing, to a so-called quarantine, without a possibility of a shower, without clean linen, to a dirty room with stinking mattresses that never change. The room was never cleaned, and the dirt on the walls caused nausea. The conditions were so terrible that I did not want to be present in the session although it was critical for me.

When you oppress a person, keep him half-starved, half-naked, give him the worst food, he becomes evil. And to whom? If he gets out of prison, he won’t go to the Prime Minister’s Office to steal. He will go to an ordinary citizen and spill his evil on him.

We have about 3,000 prisoners in our cells, and not all of them were born criminals. According to statistics, 15% do not commit a double crime. If they work with people, that number will increase. We’re always talking about 85% recidivism, but isn’t it better to focus on the other fifteen?

— Do you think there are people who are born criminals?

— I study psychology and I can’t believe it. Conditions, circumstances, they are decisive. I will also start working soon, and some amounts from my taxes will also go there [to prison]. I would very much like this money be spent on education. Quite a number of prisoners have a sixth or seventh grade education and cannot do basic work with a spade.

— By educating prisoners, does society seem to provide a higher likelihood of its own safety if the prisoner is released from prison?

— Yes. When a person commits a crime, the system focuses on the punishment rather than discovering the cause of the crime. The system doesn’t think about working on getting the person back to the public so that the latter can get back the money spent on him through work.

“If we are against the fact that a criminal should receive education and proper rehabilitation at the expense of the society, then he will just stay in jail at our expense, and sometimes stay repeatedly. We will pay that money anyway. The question is what we will get as an output.”

Individual approach to everyone

— Is the physical violence in prisons that you mentioned at the beginning of the conversation still one of the “correction” methods?

— Cases of physical violence have been rare since 2004-2005. This is also due to the visits of the representatives of the Red Cross, the Council of Europe and the Office of the Human Rights Defender.

Most importantly, something has changed in the minds of the prisoners. Before, when the correctional officers were beating, the prisoner was thinking. “You’re a man, keep quiet.” Now the prisoner thinks, “No, I am not an animal, so they beat me, and I silently tolerate.” People have started protesting, demanding the exercise of their rights, and correctional officers have become more careful.

— How is psychological help provided in prison? How many prisoners does one psychologist get?

— One psychologist has 300-400 prisoners. Some psychologists have honestly told me that they often write a conclusion based on a photo without seeing a person’s face.

But the reason is not that everyone is terrible and doesn’t care. In “Armavir,” for example, there were good psychologists in “Nubarashen,” too. But they did not manage.

A psychologist can accept two or three people a day. If more, they would need a psychologist themselves.

It takes time to analyse a conversation, find a problem, or just relax from so much negativity. The work of psychologists in correctional facilities must be strengthened, starting with the police department and ending with the Probation Service. I also do not think that they are paid well. The correction officer with a bludgeon gets more than a psychologist.

The Council of Europe is currently implementing the “Strengthening healthcare and human rights protection in prisons of Armenia” project. The project supports the national authorities in reforming the regulatory and operational freamwork of health care for prisoners in Armenia following international standards.

The project targets the following areas: the right of people with mental health problems to receive medical care in penitentiary institutions, preventive healthcare, in particular, sanitary-epidemiological and hygiene conditions and control mechanism, treatment of transmitted diseases, inpatient / specialized medical care and services in penitentiary institutions, training opportunities for the Penitentiary Medicine Centre, awareness and knowledge of prisoners about preventive medicine and hygiene.

— And what about the Church?

— The role of the Church in prisons is quite significant. Many live in the name of God and prayers. At least once a week, priests visit prisoners. They talk to the prisoners, both individually and in groups. The priest speaks about God tells the story of the Church, the Christ.

For some, it is helpful, but priests are not professionals who work with the person or the inner world. All over the world, if a person has interpersonal conflicts, he goes to a psychologist, not a priest. There are people whose problem originated in childhood, in an episode that they don’t even remember. Still, a good psychologist gets to the point where a person discovers and relives that episode, and the problem is solved.

— You and your friend want to introduce a personality assessment test in the correction system to help the psychologists in their work.

— It is a well-known MMPI test (Minnesota Multidisciplinary Personal Questionnaire — one of the most popular psych diagnostic methods for the study of individual personality traits and mental states — Kalemon), which Arsen translated and adapted to our national mentality with my support. We made three copies; Arsen’s family bore most of the expenses. Each print cost about a hundred dollars, including the cost of proofreading and printing.

By testing the prisoner with this method, the psychologist can see quite reliably what risks and problems need to be dealt with. One of the prisoners may be aggressive, the other may be associative, and the third may be prone to crime. Or, for example, in case of a tragic accident or negligent murder, the perpetrator also needs compassion. Everyone needs an individual approach.

— Suppose the Ministry of Justice approves the use of the test in prisons. But do we have professionals who can work with it?

— Rector of “Urartu” University Sedrak Sedrakyan is ready to provide space for the establishment of the Department of Correctional Psychology (a branch of legal psychology that studies the characteristics and conditions of re-education and correction of offenders Kalemon), where students will also learn working with the tests.

Mr. Sedrakyan sent a letter of motion to the prison and the Ministry of Justice requesting that Arsen be transferred to a semi-open regime to head the Chair. Arsen has already defended his doctoral dissertation and is published in psychological journals.

Arsen and I conducted the test with 180 prisoners. Many did not read the test correctly. Everyone knew how to read, but some did not understand the meaning due to lack of education, and Arsen or I explained.

— How do you feel about different workshops in prison? Do prisoners learn something there that, in addition to psychological recovery, they may need as a way to earn money after being released from prison? I saw ceramic works in the probation service. There also was a shop at the Vernissage where various items made by prisoners were sold.

– These groups are re-socialization projects, and don’t bring money. Yes, there is an exhibition-sale once a year, and if something is sold at that exhibition, there will be some money. I was once present at the presentation of my book. There were thirty or forty prisoners there, but works worth of about 7,000 drams were sold.

I will bet that if a person gets out of prison, he will not even touch the clay. And then they don’t teach in those groups to get quality. I wouldn’t give a hundred drams for that work.

Prisoners usually go to these groups only to collect parole related scores. It would be better if the money [which is spent on the specialists running the circles] were spent on real education. But they don’t want to spend money or time on it.

For example, for more than three months, Arsen taught English to the prisoners in “Nubarashen.” They provided a room with chairs, tables, and a blackboard. Twelve prisoners have expressed a desire to participate twice a week. Arsen found the books himself. He held the classes and the exams.

And suddenly, there was an order from the Board to ban those classes, because Arsen does not have the appropriate education to teach. He is from Beirut and speaks fluent French, English, Arabic, and Armenian. He speaks English even better than some graduate teachers. He had students who had studied English in a prison group before becoming his students and didn’t even know the alphabet.

— What happened to the students?

— Arsen continued to teach remotely. The employees took and brought the papers with tasks and homework, but very soon, only I remained. Everyone got tired of remote learning, especially when the employees were losing the papers either intentionally or because of negligence.

In 2006-2007, Arsen spoke with his brother to finance the renovation of five empty rooms on the sixth floor of “Nubarashen”, closely connected to the yard. Arsen’s brother had to bring some woodworking machines. Some prisoners could work with wood and teach others.

Arsen even wrote a project proposal, and the brother said he would organize the export and sale of finished products in Europe. According to the project proposal, about a hundred prisoners would be employed. They could even make small wooden sculptures in their cells. They could work together on sculptures, it would be a real profession, and after leaving, they would be able to work in workshops.

Everyone was happy. The prison administration said “no.”

The guards had to take the prisoners in the morning at half past nine and bring them back at five or six in the evening. I think they refused to avoid this movement. It turns out that the employees are too lazy to work to keep the prisoners busy.

Sometimes the prison officers were not enough in number to take us for a walk. And they just didn’t take people out. That was how the problems were solved.

Freedom without documents

— Did you serve your term until the end or were released on parole, what awaits you?

— Recently I spoke about this at the police station. The local policeman phoned me and was calling for the fourth time. I asked him how I should get there if they didn’t yet give my passport, I don’t work, should I walk for ten kilometres.

Thanks, God, my parents, and my brothers help me until I find work. However, some people get out and have nothing. It is not that they cannot adapt, but that they are not given that opportunity.

My passport was given a month and a half later. It’s paperwork. Others may get theirs even later. Look, I came out with no job, no document, and no money. Let’s say the family turned their back to me. What are my options for existence?

— To beg for money, to steal something and sell it, to dig up trash cans. In all three cases, you are not seen as corrected in the public eye.

— Yes. Thus, a person is being released and cannot integrate with the public. Thus, 85%. What do they do? They commit a crime again and get back to prison. When I was in prison, I got angry with those who returned, “are you crazy, or?” They kept telling me, “you will see when you get out.” I got out, and I saw it.

I want to suggest to the Probation Service that prisoners released on parole continue to receive money from the budget for two or three months as if still serving their sentence. Until they get a passport, they won’t find a job. You can’t even get a job as a janitor.

At the moment, the Council of Europe implements a project to help the national authorities to support the probation concept in practice, by providing the necessary legislative, institutional and operational basis, thus contributing to the increase of public security and the administration of justice.

— You are the first life prisoner to be released under the supervision of the Probation Service. Probation service begins the work still in prison. The probation service provided to you a positive opinion, as opposed to prison, isn’t’ it ? How was their work going carried out?

— 80 days before applying for parole, the Probation Service has time to meet the prisoner and the prisoner’s family for a few times.

They came to me twice, and were asking questions, what I will do when I get out, and how do I treat the crime I committed. They were assessing my behaviour, encouragements, penalties, contacts with the staff.

The prison gave a positive description when it sent the papers to the [Punishment Execution] service. But the Service considered that my article was heavy, and there was a risk of recidivism. I think they were more concerned with their “non-functioning” than with the likelihood of recurrence. I mean, they weren’t sure they worked with me enough to correct me.

Until last year, the issue of getting a release on parole was generally taboo. During the former times, when I applied [for parole], both the prosecutor and the judge kept telling me that there is an order from above not to release the lifers. There should be an order from the President’s Office. I said that I was not such an important person for the President’s Office, and that there was a law. And they were telling me, “the law is the law, but the top leadership is the top leadership.” But in 2018 we had a revolution, in 2019 the heads of the Probation Service changed, and this time they did everything according to the law.

What are you going to do?

— I want to complete my studies, get a job, promote the test in correctional facilities, and participate in the opening of the Chair of [Correctional Psychology]. I also want to go around the military units, share my story with the soldiers, tell them what, for example, a stupid argument can lead to, and in any way contribute to the prevention of internal crimes in the army. I have already been to one military unit, the another visit has been postponed due to the epidemic, but I hope to carry ion after the restrictions are lifted.

The article was created in partnership and with support from the Council of Europe, Armenia.

Become a Patron

We are building a community of affectionate, non-judgemental people with an open mind. If you want to support our work of investigating the deepest social issues through personal stories of real people, the best way is to join us and become a Patron.

Text is over, story goes on

Here on Kalemon, we bring unspoken social issues to life in the form of narrative stories. Our mission is to create social impact by breaking taboos and freely discussing important matters, such as violence, poverty, discrimination, parental and medical ethics, and so on.

Kalemon is a non-profit online media that exists thanks to the financial support of individual people. Small, but regular donations from our readers help us write articles, train & recruit new authors, maintain and develop the website.

As little as 2 dollars per month can make a difference. Thank you!